I have seen these two techniques conflated in the media and even in academic papers, so I wanted to write this post to clear this up. I can see where the confusion comes from, after all, they both involve family and DNA. However, they are very different techniques and the differences are very consequential.

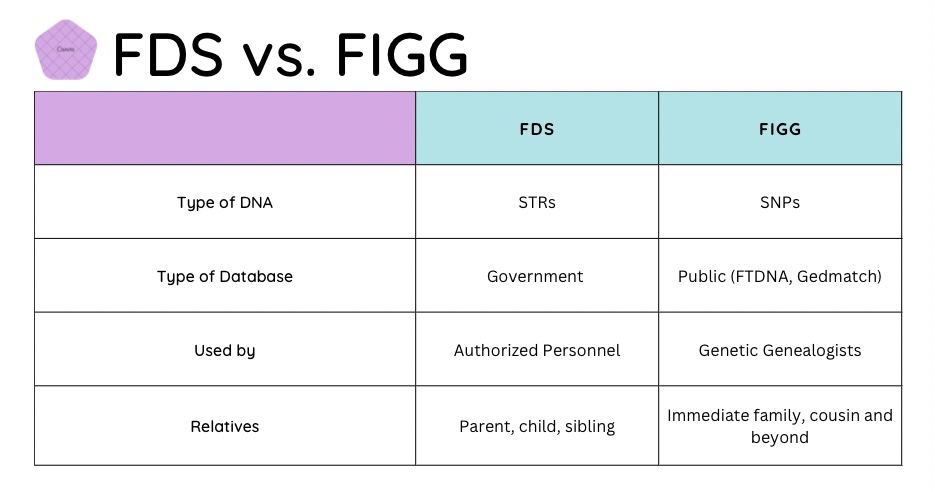

The first difference is the type of DNA. Many people don’t understand that the DNA used in government databases is not the same kind of DNA used in direct-to-consumer (DTC) DNA tests. DNA is DNA right? It’s all made up of 4 letters, repeating in different combinations. The difference comes with how we look at it. Government databases measure DNA in STRs (short tandem repeats), and DTC test measure DNA in SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms). Short Tandem Repeats are segments of DNA where the same pattern repeats over and over again, and we count how many times it repeats. We do this is many different spots (in the US the current amount is 20 places) and end up with a 20 digit number that is unique to a person. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism is a single place where the nucleotide (DNA letter) is different. About 600,000 SNPs are used when measuring DNA for a DTC test. As you can see, even though we’re measuring the same thing (DNA), we’re measuring it in two different ways that are so radically different from each other they can’t be compared to each other.

Next is the type of database. Familial DNA searching, where authorized, is done in a country’s government-run DNA database (Canada does not allow its use, and it isn’t allowed in the US’s National DNA database, but it is allowed in some states). FIGG is done in public DNA databases, namely FTDNA and Gedmatch. I will digress here and state that it also does a disservice to the field when people say “ancestry databases” or outright say that Ancestry and 23&me are being used for FIGG when they are not. The reason why it is important to distinguish between government databases and specific public databases is that FIGG relies on public trust. If you commit a crime and are required to put your DNA in a government database, there isn’t much you can do to avoid that. However, if you have a DNA test done and you don’t want to submit your DNA to databases that allow for law enforcement use, you have a choice in the matter. It’s important to reassure the public that their DNA is not being used without their consent, and where they should be putting their DNA if they do want to help.

The type of people who do familial searching are authorized personnel. Generally forensic DNA scientists are the ones doing the analysis, and their work is presented to authorized law enforcement. No one, even within law enforcement, can just decide one day to access a government DNA database. It’s highly regulated. FIGG, on the other hand, is currently the wild west. Anyone can call themselves a genetic genealogist and hang up their shingle. While the topic of legislation and regulation of FIGG is a whole other post, suffice to say that this is another huge difference between the two techniques.

The limits of how distant a relative that can be found with the technique is another difference. Familial DNA searching can only locate very close relatives, either a parent, child or sibling. While FIGG is more successful with closer relatives, it still can work with more distant relatives than familial searching.

I hope this summary of the differences between the two techniques has been informative. In order to have valuable discussions surrounding the use of these techniques, it’s important that we’re using the same language to talk about them. Spreading misinformation, even unintentionally, also erodes public trust, so it’s important to get this right.

Leave a comment