I talked about why citations are important in this blog post. Today I’m going to talk about citation basics, to make it easier to understand how the components of a citation fit together.

Let’s start with the very basic of basic citations: a book.

Tom Jones, Mastering Genealogical Documentation (Arlington, Virginia : National Genealogical Society, 2017).

We can learn everything we need to know about this source, to help us evaluate it, just by looking at the citation. We can see that Tom Jones wrote it, and anyone in the genealogy world knows how esteemed he is. We can see that it’s been published by a real publisher, which also adds to the value as it has likely been reviewed many times at many levels to make sure it is accurate and well-written. We have a date of publication, which also tells us about how reliable the source is. For sources about events, things that have been published closer to the event might be more accurate as they aren’t relying on broken telephone messages passed down through history. It may also reveal a bias, such as a colonialist mindset. Our specific research question will help us to properly evaluate the date and what it means, but you can see why it’s important.

The components of a citation are the famous Ws. WHO, WHAT, WHERE, and WHEN.

WHO: the author, Tom Jones

WHAT: the book, Mastering Genealogical Documentation. Note that the convention for the title is italics.

WHERE: Virginia, where it was published

WHEN: 2017, when it was published

Note also that a reference citation is like a sentence: it begins with an indent (which technical limitations are causing not to show up), all the elements are separated with commas, and it ends in a period.

Every single citation is a riff off of this basic one. Every. Single. One.

Let’s say we want to get more specific, and refer to a chapter in this book:

Tom Jones, “The Purpose and Nature of Genealogical Documentation,” Mastering Genealogical Documentation (Arlington, Virginia : National Genealogical Society, 2017).

The title of the chapter is in quotation marks, to let us know that this is a part of the whole, which is in italics.

If we want to reference a particular page rather than a specific chapter:

Tom Jones, Mastering Genealogical Documentation (Arlington, Virginia : National Genealogical Society, 2017), p.7.

We could reference multiple pages by changing that to p. 7-10.

A website citation is very similar. For example, if I want to reference my blog:

Jennifer Wiebe, Jennealogie (https://maltsoda.wordpress.com : accessed 20 July 2022).

Again, we have the WHO, myself who writes this blog, the WHAT, the title of the blog (in italics), the WHERE (the URL of the blog) and the WHEN (the date I viewed the blog).

If I want to reference a specific post, it’s just like a chapter in a book:

Jennifer Wiebe, “Cite Your Sources,” Jennealogie (https://maltsoda.wordpress.com/2019/05/24/cite-your-sources/ : accessed 20 July 2022).

Citations became a lot more complicated when the internet came around, because now we don’t need the physical copy of the book, we can look at the book online, and this has to be reflected in our citation. To accomplish this, we use LAYERS. Each of our layers answers the W questions, and they are separated by a semi-colon.

For example, this random book I found on Archive.org:

Pamela Pollack, compiler, The Random House Book of Humor for Children (New York: Random House, 1988); digital image, Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/randomhousebooko0000unse_c2n3 : accessed 20 July 2022).

Note that when I’m starting my second layer I write “digital image” so people know I’m physically looking at a picture of the book, not just a transcription that someone made.

My WHO is Pamela Pollack, the compiler of the book. I don’t have a WHO in my second layer since Archive.org doesn’t really have an author. I could say that the author is Archive.org, but since it’s also my title, I don’t want to repeat myself.

My WHAT is the name of the book and also the name of the website where I viewed the book. Both are in italics. If I wanted to reference a specific chapter or page number, I would add it to the first layer as I did if I was holding a physical copy of the book. To the second layer I could also add the image or page number on the website, which may vary from the page number in the physical book.

My WHERE is New York, where the book was published, and also the URL for where I would find the book online.

My WHEN is when the original book was published, in 1988, and also the date that I viewed the website.

Let’s take a look at another example, using a marriage record:

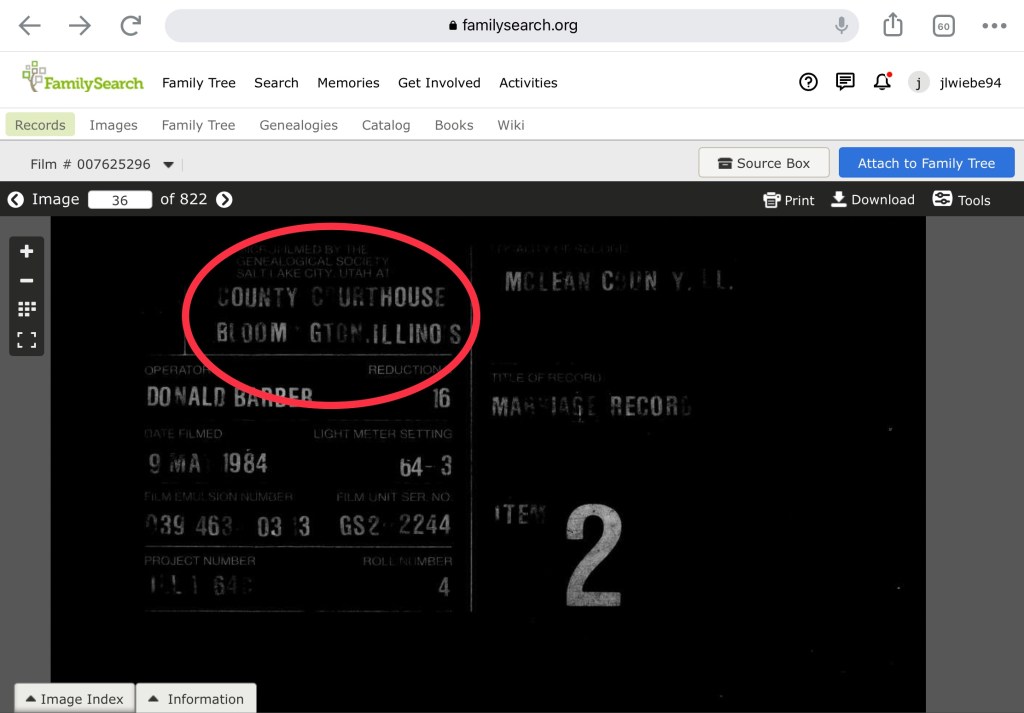

McLean County, Illinois, marriage record, page 178, license 12214, William Beverage and Myrtle McCracken, 23 Dec 1896; image, “Illinois, County Marriages, 1810-1940,” FamilySearch, (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L924-RDQ8?cc=1803970 : accessed 18 July 2022) > image 1 of 1; citing county courthouse, Bloomington, Illinois.

The marriage record comes from a county marriage register, so even though it’s from a book it’s not going to be cited the same way because it was never published. My first layer WHO is the county, the creator of the book. My first layer WHAT is the marriage record, and I’m not going to repeat the WHERE (the county) since it was included in the WHO. The WHEN is when the marriage took place.

My second layer is from the website where I saw the image. Again, the WHO is missing because FamilySearch is both the WHO and the WHAT. I put the specific database where the image was found in quotation marks since it’s a smaller part of the bigger whole. Again, the WHERE is the specific URL that will take me to the image, with a waypoint showing that it is the only image I want to look at. The WHEN is the date I viewed it.

Let’s talk about the third layer. First, this layer exists because FamilySearch doesn’t have the document in their possession, and we need to know who does. Second, we know that the county created this record, which gives us insight into how reliable it is. But who has been the caretaker of this record since then? This is also important in establishing reliability, since if it was from someone’s basement, maybe the courthouse didn’t actually create this record. Or maybe the caretaker altered things in the record while it was in their possession. This third layer gives us an opportunity to say “don’t worry, this record has been hanging out at the county courthouse, so it’s been properly cared for!”

This last layer can be tricky to fill out, so here’s how to find it on FamilySearch:

Sometimes if you click on the information/citation for the record, it will tell you where it got the information.

In this situation, I felt that it was not specific enough. So if you click on the little squares:

It will zoom out so you can see many of the images of the collection at a time:

Scroll up, until you come across a page that is obviously not scanned from the book:

Click to view that page, and it will usually tell you where the person was doing the microfilming/digitizing. Voilà! Add that information to your third layer.

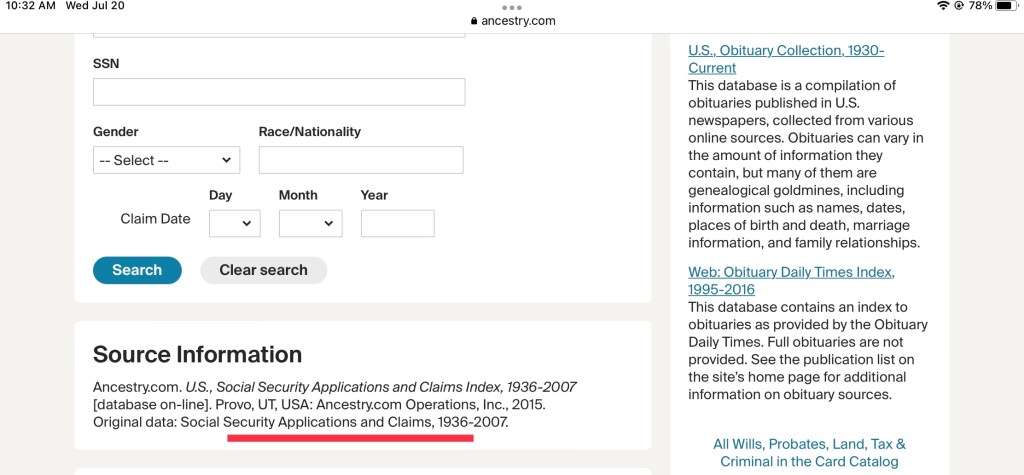

Ancestry can be even trickier to find the info and is usually pretty vague about the “source of the source.” Here’s one example:

Did you know the title underneath the name is hyperlinked?

Click on it, and it will take you to the page where you can search the entire collection for that database. Scroll down and it will give you some original data information:

It’s not much but I’ll take it.

I hope this has been helpful to understand citations and how to craft them!

Leave a comment