Whether you’re talking about unknown parentage, Unidentified Human Remains (UHRs), or Forensic Investigative Genetic Genealogy (FIGG), the steps to use DNA to solve them are pretty similar. I’m sure there’s as many processes as there are people, but I like to think of it like a jigsaw puzzle. Every DNA match is a piece of the puzzle. I always do the outside first, then sort pieces, and see what I can put together. It’s a great feeling when you figure out where a cluster of pieces fits in the puzzle, and it’s the best feeling when two clusters join together.

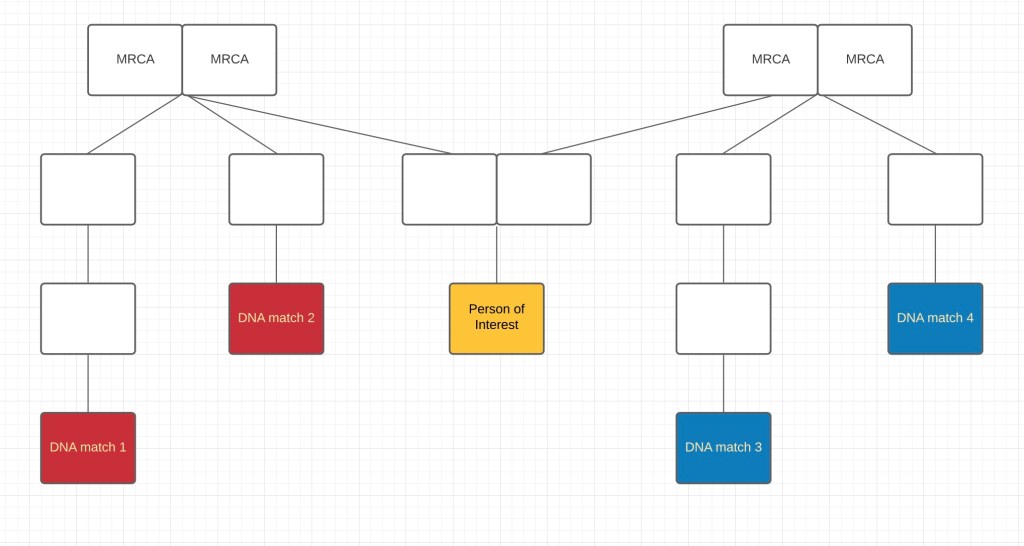

The edge pieces are like your biggest match; it kind of frames the case. If you’re lucky, the edge pieces will also be part of a cluster of pieces, like a big red flower in the corner of the puzzle. If you can figure out how all those pieces fit together, you’re in business. All the DNA matches in a cluster connect to a most recent common ancestor (MRCA).

Once you’ve got those DNA matches sorted, you can work on putting together another cluster and then look for clues for how the two clusters fit together. Sometimes it requires lots of building down (woe to you if there were many children, or if the common ancestor is very far back, or both).

Let’s say you’ve identified what you think is a set of grandparents as your MRCA. This means that the parent of your person of interest is the child of this MRCA. You would then build back trees on all of the spouses of all the children of this MRCA, since the other parent will likely have DNA matches who won’t match the initial cluster (let’s say it’s a blue flower in the other corner). In this example, I found that the blue cluster connected to a spouse of one of the children of the red matches’ MRCA. The descendant of that couple who connect those two trees is our person of interest.

In my example, the person of interest is the grandchild of two identified MRCA couples. But if we’ve only been able to identify great-grandparents, we will again have to find DNA matches that connect to yet another spouse, as in this next example.

As you can see, the red and blue DNA matches have identified two sets of great-grandparents of the person of interest, but since both those are on the same side of the tree, we need to narrow it down more. One of the grandchildren of those two MRCA couples has a spouse that connects up to the green DNA matches (dotted lines were used to make it easier to see the lines crossing, but have no other relevance). As you can see, the further back the MRCAs are, the more complicated the tree is, the more work you have to do to identify clusters, and the more tree-building you have to do.

In an ideal world you’d have 4 perfect clusters connecting the person of interest to each of their 4 grandparents, and marriage records tying a each set of grandparents together, as well as a marriage record tying the parents together. More often than not this is not the case. In adoption cases especially, the parents aren’t usually connected to each other. The examples I’ve given are a best case scenario, but often things don’t go to plan.

Things that can cause problems and require different strategies:

Imagine a puzzle where all the pieces are similar colours. When dealing with endogamy, clusters are not very useful.

What if someone took some of your puzzle pieces and painted over them? If there was an adoption or a non-paternal event anywhere in a match’s pedigree, you won’t be able to connect them up to other matches in their cluster. These types of events occur without people being aware of them, so even if you were fortunate enough to find a tree for a DNA match, there is no guarantee that their tree is correct from a biological point of view.

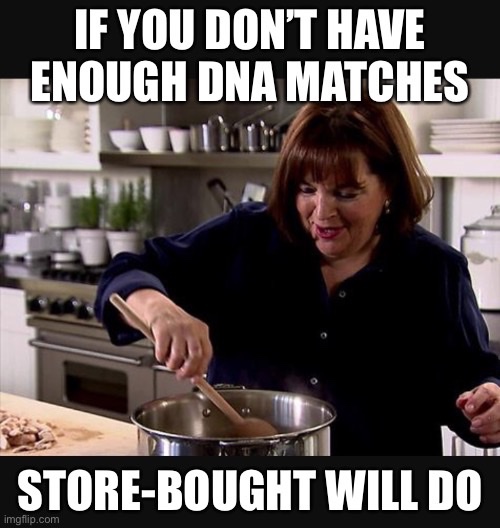

You can also imagine a puzzle missing many of the pieces. In cases where there are not many DNA matches and/or the matches are very distant, putting the puzzle together can be impossible. In some cases we can create our own DNA matches by asking for cousins of our current DNA matches to test, called “reference samples” or “target testers” (although since we don’t want to make people feel targeted, reference sample is the preferred term). It’s not ideal and not everyone is interested in being a reference sample.

While the use of DNA has advanced our abilities to discover biological family and identify UHRs and suspects in cold cases, the path isn’t always as smooth as we’d like. Still, if we wanted to put together puzzles without the challenge, we’d still be doing the 25 piece puzzles we did as children. There’s a special feeling that comes with completing the challenge of a more difficult puzzle, and I love it.

1) Jennifer Wiebe, digital photo, Puzzle, April 2022, author’s files.

2) Jennifer Wiebe, digital photo created with LucidChart, Cluster of matches with their MRCA, April 2022, author’s files.

3) Jennifer Wiebe, digital photo created with LucidChart, Tree Triangulation, April 2022, author’s files. Tree triangulation should not be confused with segment triangulation.

4) Jennifer Wiebe, digital photo created with LucidChart, More tree triangulation, April 2022, author’s files.

5) Jennifer Wiebe, digital photo created with imgflip meme generator (https://imgflip.com/memegenerator/64141129/Ina-Garten : accessed 21 April 2022), Make your own DNA matches, April 2022, author’s files.

Leave a comment